Van Gogh and Collective Nostalgia

An essay exploring creativity, madness, and mental health through the cultural myth and collective nostalgia surrounding Van Gogh’s life and art.

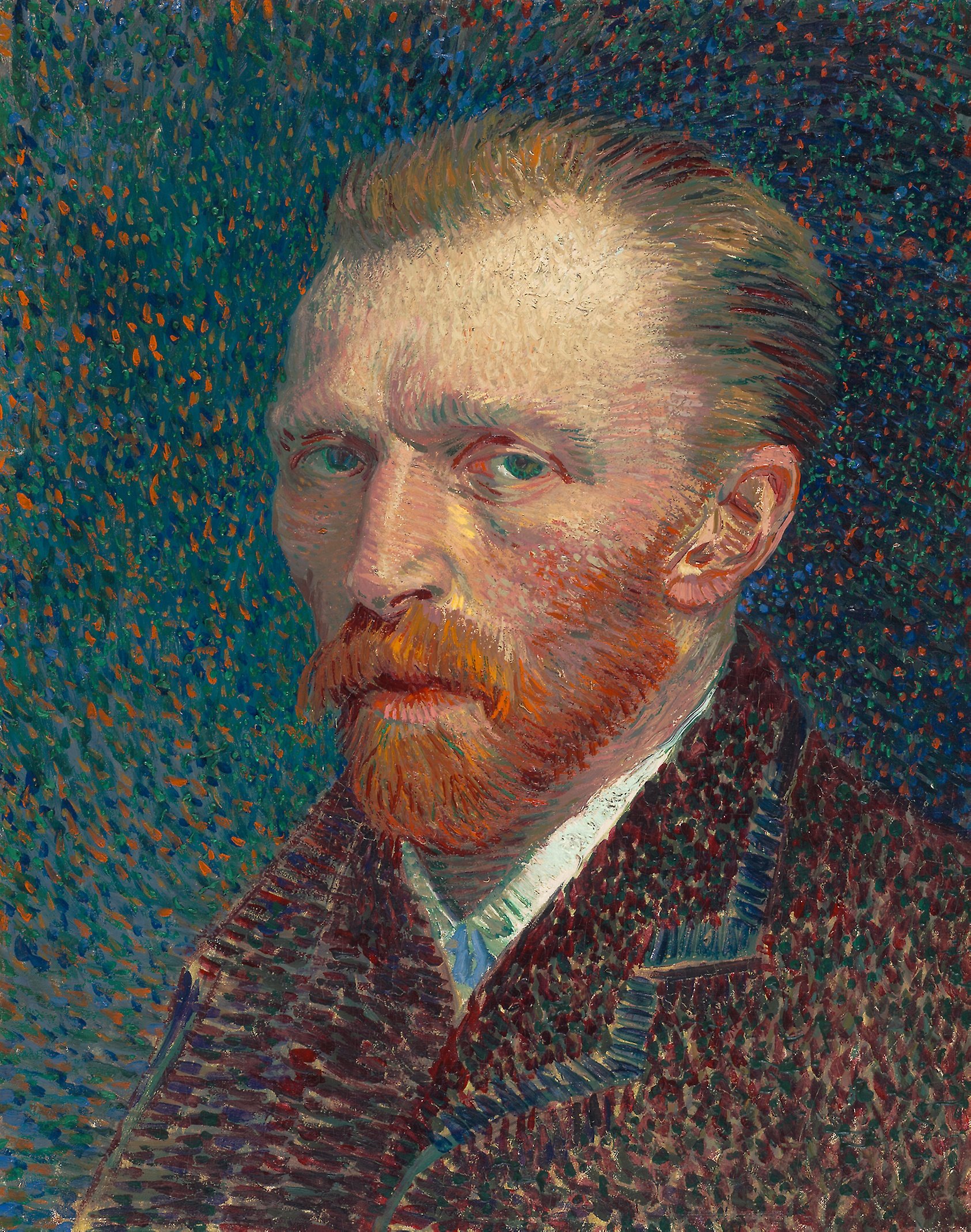

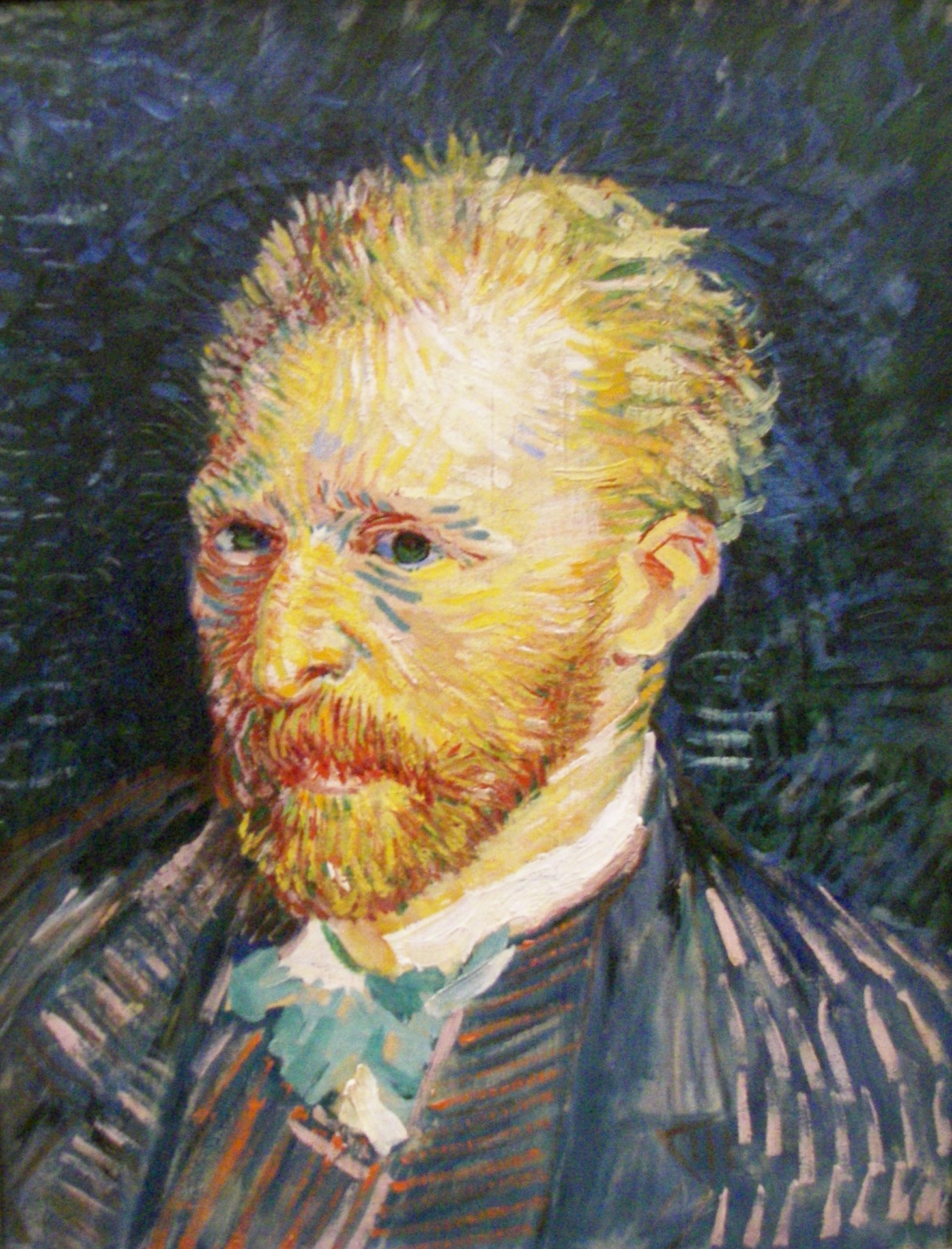

In 1887, Van Gogh painted a series of self-portraits each representing an alternative perspective on who he was; yet the one that is most present in the collective memory of Van Gogh—the self-portrait with a bandaged ear—is not amongst them. It was painted in the year 1889 during his recovery from his infamous episode of self-mutilation when Van Gogh cut off his own ear. As one of the most celebrated famous artists in Western culture, this is the version of him that we most readily remember. Van Gogh is mythologized as a visionary born ahead of his time who was tortured by his creative genius. His vibrant sunflowers and starry night sky are placed beside his bandaged ear, as though the ear had to be cut off to expose such colours to the world. We believe that Van Gogh’s mental instability allowed him to see the world in a way that others cannot see and admirers from across the globe seek out his work to glimpse into his unique perspective that has been immortalized by his paintings. The traces of his unique, colourful perspective surround us in the present far beyond the enclosed walls of the museum in letters, souvenirs, postcards, films, and immersive experiences.

The array of attempts to constantly repeat the unrepeatable through the reproductions of Van Gogh’s work and narrative points to a “strange historical vanity [and a] counterfactual compassion” (Boym, 2001: 6 & Lee, 2018). Hidden beneath the nostalgic, collective memory of Van Gogh as a misunderstood genius born ahead of his time lies a myth of reassurance. The cultural memory of Van Gogh in Western society signals an attempt to collectively reassure ourselves that progress has been achieved. In the impossible, mythical memory of Van Gogh, it is imagined that if he had been born today then we would have bought his paintings, we would have gotten him the right therapeutic care, and we would have saved him (Boym, 2001: 14 & Lee, 2018). As the nostalgic, collective memory of Van Gogh ruptures the past from the present through the reassurance that his suffering would have been eased if only he had lived today, it simultaneously romanticizes his individual suffering as an integral aspect of his creative genius and artistic productivity. The messy, collective memory of Van Gogh as both retroactively saved from suffering in the present and as necessarily suffering for his art in the past exposes the contradictory perception of mental health in present-day Western society (Boym, 2001: 54). Remembering Van Gogh through his iconic self-portrait with a bandaged ear demonstrates a continual emphasis on the individual, unique pathology of mental illness, rather than a confrontation with systemic issues in Western society linked to mental well-being. Despite a discourse acknowledging mental illness as a collective, social problem, it is treated privately on a radically individual level and remains hidden from daily life. Mental illness is no longer delineated by the firm, visible lines of madness and madhouses of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; instead, it has been rendered invisible by a myth of progress in the twenty-first century. We believe we have properly confronted the issue of mental health in the present because the asylum belongs to the ‘distant’ past, while mental illness lurks in the shadows of society behind the closed doors of private psychiatry clinics and hidden within medicine cabinets of private homes today. Mental illness today only becomes as visible as Van Gogh’s bandaged ear when productivity ceases. The myth of progress hidden within the collective memory of Van Gogh as born ahead of his time reveals the way in which Western Europe and North America anchor a collective, western identity in a reflective nostalgia, which disguises the lingering elements of systemic violence in Western society today and renders mental illness a problem of the past that has been properly addressed in the present.

Van Gogh has been heralded as “the ideal of the modern artist” and as a cultural icon of Western society (Lee, 2018). His most famous works of art rest immortalized on display within museums in New York, Paris, Amsterdam, and London. He was a man born in the Netherlands who moved to the cultural epicentres of London and Paris as an artist. He most famously spent his days painting in the countryside of the south of France with Paul Gaughin before cutting off his own ear. In many ways, Van Gogh exemplifies the modern condition through his mobility throughout Europe, his lamenting of urban life, and his idealization of pastoral figures (Martin-Barbero, 1937: 194-195). Moreover, he embodies the Western “ancient notion of creativity as a species of divine madness,” as he is remembered as an artist of unbridled passion driven by the creative forces of the unconscious (Lee, 2018). His art is perceived as both misunderstood in his own time and as a colourful glimpse into a timeless perspective of a unique, creative genius. As Van Gogh is remembered through his iconic self-portrait with a bandaged ear, the Western cultural memory of Van Gogh reveals itself as a form of reflective nostalgia. Looking upon this self-portrait of a tormented artist, we mourn his suffering and the “impossibility of a mythical return” to retroactively rectify the travesties of his life (Boym, 2001: 14).

The abundance of representations and re-representations of his life and work in Western culture reveal the insatiability of a nostalgic desire to affectively experience a “history without guilt” in which Van Gogh’s genius was appreciated and his illness was treated (Boym, 2001: 5-6). The variety of “repetitions of the unrepeatable” demonstrate the way in which nostalgia acts as a “desperate craving for history, while reinforcing the past as ‘a vast collection of images’” (Boym, 2001: 6 & Grainge, 1999: 632). Since 1948, at least nine different movies have been produced about Van Gogh. His golden sunflowers blossom on coffee mugs and children are encouraged to paint six-minute versions of Starry Night. The collective memory of Van Gogh is not defined by a single painting, film, or souvenir. Rather, Van Gogh, his work, and his life offer common points of reference for Western society constituted by individual recollections, which manifest in non-teleological cultural myths. Though collective memory is fragmented by individual recollections, “collective memory represents [a] group’s most stable and permanent element” and forms the substance of a group’s identity (Whitehead, 2009: 129 & 131). The collective memory of Van Gogh as a misunderstood, creative genius grounds the cultural myth that Van Gogh was born ahead of his time. Cultural myths are understood here as the recurrent narratives in a given culture and are the “shared assumptions that help to naturalize history” (Boym, 2001: 54). Through different “fetish possession[s]” and a multitude of representations of Van Gogh’s narrative, Western society nostalgically and collectively consumes history without guilt through the cultural myth that Van Gogh was born ahead of his time.

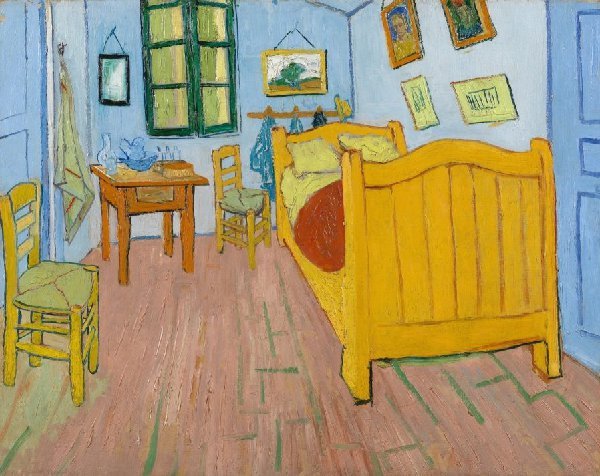

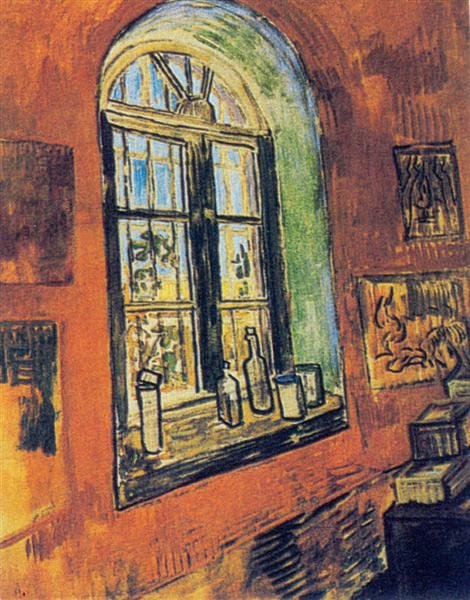

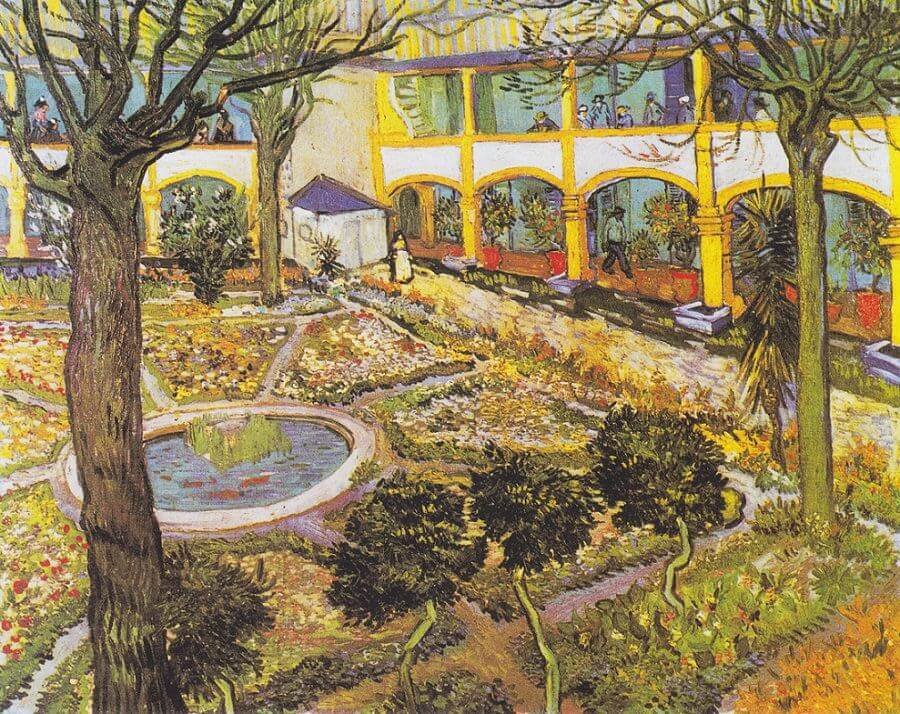

The shared assumptions in the cultural myth of Van Gogh as both an artist born before his time and as an artist who had to suffer in order to bring his creative vision to life construct the memory of Van Gogh through acts of forgetting. While reflective nostalgia “cherishes shattered fragments of memory,” the shadowy underside of memory reveals what is forgotten (Boym, 2001: 49 & Whitehead, 2009: 14). As nostalgia attaches temporality onto spaces, the memory of Van Gogh is placed in the yellow house in Arles where he lived with Paul Gaughin and where he violently cut off a piece of his own ear in 1889; however, the shadowy underbelly of the asylum in which he painted some of his most famous works is not remembered with the same illumination (Boym, 2001: 49 & Whitehead, 2009: 10). Guiding the posthumous memory of Van Gogh, a French art critic named Albert Aurier famously wrote about Van Gogh after his passing that Van Gogh’s art stood out for its “excess of nervousness [and] violence in expression” (Van Tilborgh, 2016: 26). The association between Van Gogh’s violence, art, madness, and death persisted through the ambiguity of his illness, which aligned itself with the dignity of the unknown in romanticism of the twentieth century and the Symbolists in Paris during the avant-garde movement who considered the “mentally ill [as possessing] a visionary and exalted gaze” (Van Tilborgh, 2016: 22). This perception of Van Gogh’s art pervaded cultural memory after his passing and connected his artistic expression with his mysterious, violent illness and his mysterious, violent death.

In the late 1800s, around the time of Van Gogh’s mysterious and violent death, Freud’s concept of the timeless unconscious also emerged (Whitehead, 2009: 91). As both memory and madness are “historically conditioned,” the memory of Van Gogh’s artistic genius was shaped by a perception of the spontaneous, creative forces of the timeless unconscious in such a way that simultaneously exalted Van Gogh’s madness to the realm of divine inspiration and stripped Van Gogh of individual agency (Whitehead, 2009: 4; Van Tilborgh, 2016: 22). The incomprehensibility of Van Gogh’s violent act of self-mutilation has been reformulated through a cultural myth that both narrativizes and “harmoniz[es] the disruptions of trauma” to tell the story of a misunderstood, creative genius born ahead of his time (Whitehead, 2009: 116-117). Recounting Van Gogh’s story through his episode of self-mutilation as the focal point emphasizes the singular, dramatic act of self-mutilation and exalts ‘madness’, while obscuring the constant, slow “banality of real mental illness” (Cross, 2010: 131). In this way, the collective memory of Van Gogh simultaneously romanticizes mental illness while denying the realities of its lived experience. The comprehensive narrative forgets the incomprehensibility of mental illness and instead plots unreason onto the framework of reason (Foucault, 1965: 83). As Foucault argues, “the Reason-Madness nexus constitutes for Western culture one of the dimensions of its originality,” and it is within this framework that the stable, collective memory of Van Gogh is shaped (1965: xi). Western society anchors its collective identity in the age of Enlightenment, which redefined man through the capacity for reason; while the “animality that rages in madness dispossesse[d] man of what is specifically human in him” (Foucault, 1965: 73-74). In the eighteenth century, “unreason was hidden in the silence of the houses of confinement,” while madness was elevated to the level of spectacle and “glorified scandal” (Foucault, 1965: 70). This paradoxical tension in Western society of denying the fundamental human experience of unreason, while glorifying the scandal of madness points to the way in which collective memory, “knowing too much about madness, forgets it” (Foucault, 1965: xii).

As forgetting is an “active agent in the formation of memories,” the memory of Van Gogh as an artist who suffered uncontrollable passions for his art had to actively forget the ways in which mental illness disrupted his methodical artistic process (Whitehead, 2009: 121). We forget that it was only in recovery and through extraordinary discipline—rather than in the throws of mental illness and untamed passion—that Van Gogh was able to paint so prolifically. The iconic image of Van Gogh’s self-portrait with a bandaged ear recalls the violent “spectacle of madness” of his dissociative episode. However, the bandage itself—in the context of recovery—fades out of collective memory into the “secrecy of the asylum” (Foucault, 1965: 67-68). It was from within the confines of the asylum, marked by the ‘non-productive’, ‘idle’ time of recovery, that Van Gogh brought to life his Starry Night (Scull, 2016: 254). Yet the narrative most frequently recounted is that painting was a natural side effect of his uncontrollable passions rather than a product of his dedication to his art or as an integral part of the slow, heavy process of recovery. The “systematic forgetting” of the process of labour is deeply embedded within the structure of modernity and capitalist production of the present-day (Connerton, 2009: 88). ‘Madness’ has been defined by idleness or a general “incapac[ity] of productive labour,” and the mode of forgetting that pervades the current cultural memory of Van Gogh’s mental illness transforms the process of labour of his art into a natural consequence of the simultaneously glorified and stigmatized “animality of madness” (Scull, 2016: 122 & Foucault, 1965: 78). In this way, the unbridled passions of insanity themselves are remembered as productive, while the banal, daily struggle of the lived experience of mental illness is overshadowed by its spectacle.

The iconic image of Van Gogh’s self-portrait with a bandaged ear recalls the violent “spectacle of madness” of his dissociative episode and the exposes the visible differences between the ‘mad’ and the ‘sane’ (Foucault, 1965: 67-68 & Cross, 2010: 131). Yet as Western society moved away from the demarcated spaces of the asylum and the visibly ‘mad’ towards the “constitution of madness as mental illness” at the end of the eighteenth century, the clinical gaze of psychiatry began to disguise the defining characteristics of mental illness within the language of “scientific objectivity and neutrality” (Foucault, 1965: x & Scull, 2006: 127). While the language in Western society shifted from lunacy, madness, and insanity in the 1800s to a language of mental illness, disease, and health in the present, mental illness remains defined by “behavioural norms” (Grob, 1977: 33). Just as memory is historically conditioned, so too, is mental illness. As the cultural myth of Van Gogh born ahead of his time ruptures association between the violent past of mental illness from the clinical approach of the present, the culturally evaluative dimension of how mental illness is approached is masked by a screen of scientific objectivity and an emphasis on “individualistic and pathological terms” (Scull, 2006: 127). In the same way that the collective memory of Van Gogh’s timeless, unconscious, creative genius de-contextualizes his artistic talent, the clinical gaze de-contextualizes and de-politicizes the cultural formations of mental illness by throwing those cultural formations sideways into the universal, empty, homogenous time of progress and modernity (Scull, 2006: 127 & Boym, 2001: 19 & Anderson, 1983: 24). We forget that nostalgia was originally defined as a mental illness; we forget that hysteria and electroshock therapy were common practice well into the twentieth century; we forget that the asylum was exported through colonialism and viewed as a mark of “civilized society” (Boym, 2001: 10 & Scull, 2016: 200 & Fanon, 1961: 250). The spectacle of madness in the collective memory of Van Gogh forgets the lived experience of mental illness and the myth of progress hidden in the cultural myth of Van Gogh as born ahead of his time forgets the gendered, racial, classicist cultural formations of mental illness rooted in Western society.

Whereas mental illness was once hidden behind the confines of the asylum, it now hides behind the myth of progress and the private practices of the clinical gaze. The clinical gaze which de-contextualizes the history of mental illness from its societal, cultural formations enables it to be perceived as timeless, universal, and objective. Though madness was once perceived as a reflection on the ills of society and as such had to be locked away behind the secrecy of the asylum, in the present, the mentally ill “regarded as both carriers of an individual pathology needing cure and collective social problem needing mastery” (Philo, 2012: 168). Mental illness has been reinterpreted through the objective language of the clinical gaze that can be mastered through medication. In the present, medication has “replaced talk as the dominant response to disturbances of emotion, cognition, and behaviour” (Scull, 2006: 126). By rupturing the association between the past and the present through the cultural myth of progress hidden in the collective memory of Van Gogh, the role of mental illness in present day Western society reveals a continued emphasis on individual pathology and an invisible definition of mental health centred around productivity, dysfunction, and modernity.

While nostalgia is a form of rebellion against the modern idea of time and progress insofar as time is conceived non-teleologically and non-linearly, the case of the nostalgic cultural myth of Van Gogh in Western society supports a myth of modern progress (Boym, 2001: 4). As progress became the marker of global time, global time became associated with economic productivity in the modern era (Boym, 2001: 15-16). The demand for productivity that has persisted in capitalist, Western, hegemonic society today has also pervaded the cultural formations of mental illness. The increased demands for constant productivity in present-day Western society have shaped the increased presence of mental illnesses such as anxiety and depression that appear to define the maladie du siècle of the twenty-first century. The clinical response of psychiatry to treat these illnesses as individual, chemical imbalances that can and should be treated with medication, rather than critically addressing the social structure of Western society, reveals the way in which the ubiquitous myth of progress denies the systemic, cultural formations of mental illness on a practical level. While Van Gogh’s act of self-mutilation became a historically public spectacle, daily acts of self-mutilation in the form of cutting—driven by the pressures of present-day, Western society—are hidden within the confines of the private sphere. The perception that mental health has been confronted on a societal level in the present renders the realities of the lived experiences of mental illness invisible, as the daily struggles with mental illness are relegated behind the closed doors of the private medicine cabinets and clinics. Despite a discourse espousing a confrontation with mental health in popular culture, the daily struggles of mental illness in Western society today only emerge into public consciousness when productivity transforms into dysfunction or death.

As we look back on madness through a nostalgic lens which narrowly focuses on the particularity of madness, we simultaneously romanticize and pity individual suffering while forgetting the systemic violence associated with mental illness in the present. By rupturing the past from the present through the myth of progress hidden in the contradictory, nostalgic, collective memory of Van Gogh as born ahead of his time, Western society structures collective, societal issues as individual pathologies of mental illness that can be mastered through medication. Despite the myth that progress has been achieved and that Western society has confronted its systemic issues and its violent past, mental health remains defined by the capacity for productivity and mental illness remains defined by dysfunction within a radically individualistic, capitalist framework. As we raise the memory of Van Gogh beyond the real through a glorified and stigmatized exaltation and the rationale of violent, creative genius for his suffering, the Madness-Reason nexus continues to anchor western identity and denies the banal realities of the lived experience of mental illness. The incomprehensible aspects of the human experience continue to be absorbed by the ubiquitous presence of an uncontested, universal, objective demand for productivity.